Interview with Alan Hodgkinson

Share

We caught up with Alan to chat about his lifetime exploration of gemmology.

What first sparked your interest in gemmology?

At 18 years old, I was posted to RAF Aberdeen for my national service and there met the Hendersons, a family of jewellers who offered me a career opportunity in their shop. So began my life in the jewellery trade. There was, however, a stipulation: I must become a gemmologist, and so two years later I was awarded the FGA with distinction.

Who was influencial in shaping your path in gemmology and encouraging you?

In 1969, I moved down to Glasgow as the trade’s first Group Training Officer of Jewellery Training Scotland Ltd with my wife Charlotte. When the grants ran out, I determined to try and go it alone.

Several of the previous directors from JTS were helpful and encouraging. I initiated a new concept in Gemmology education of two-day practical, hands-on gemmology courses. The breakthrough came when Eric Bruton, author of the classic book Diamonds, sponsored my courses in London where he was publisher of the magazine Retail Jeweller. This publication reached throughout the industry as it was free (paid for by advertisers).

The courses took off, and over the next few years, virtually all the UK trade enrolled. The next development was an invite to take the courses to South Africa. Over the following decades, I was invited to lecture and run workshops in Europe, Asia, Australia, Canada and the United States where I delivered lectures at the Tucson Gem Fair over the following 30 years. One of the spin-offs was a lecture tour of 14 American cities in 26 days!

Which gemstone do you find most fascinating and why?

Not an easy question to answer. I had some 6,000 gems in my teaching collection, and there are so many which pose intrigue and the wish to share those secrets with other gemmologists. The alexandrite from Orrissa, the first seen in the western world, was a stone I was able to share with so many gemmologists on my lecture tours. Its colour secrets are shown on pages 348-349 in the book.

What gemmological books do you still refer to?

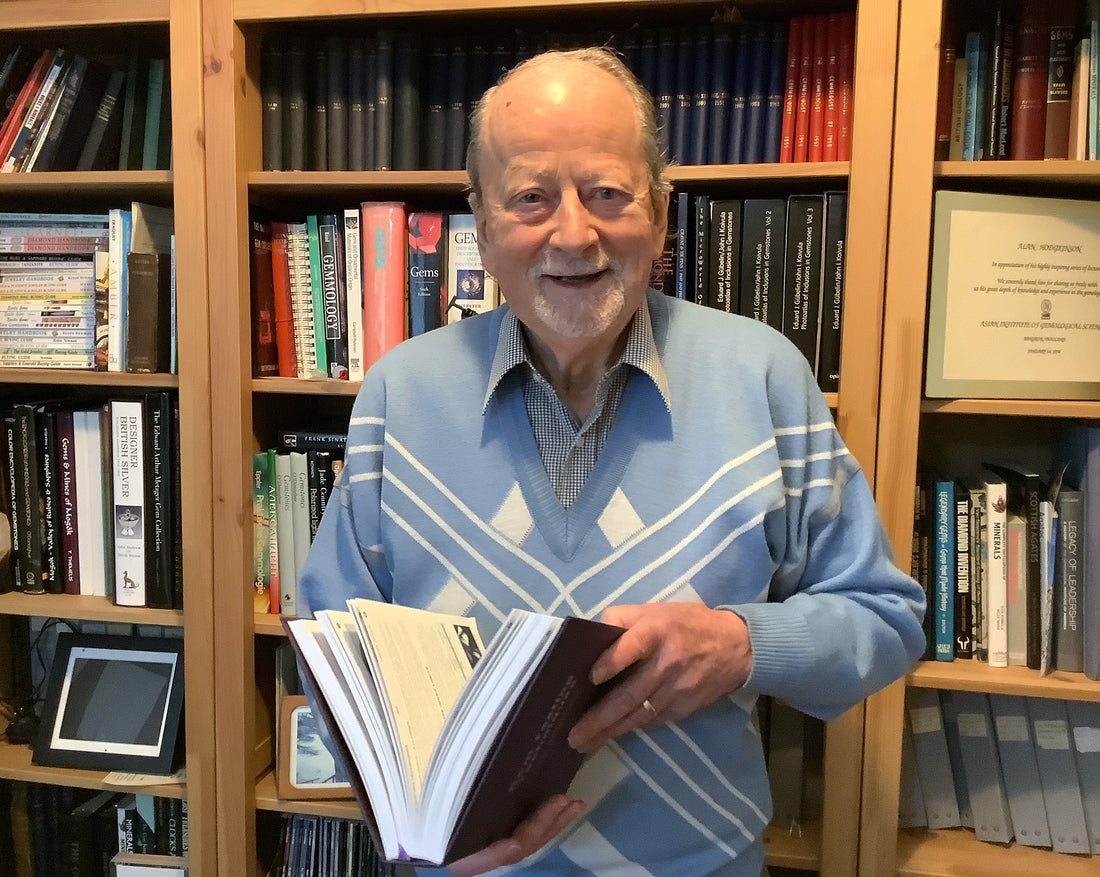

The photo of me with my gemmological library indicates what a wide field gemmology has become, but it is always a pleasure to dig out Basil Anderson's Gem Testing. His eloquent phrasing and use of the English language conveys so much with the minimum of space. What a magnanimous man, and what a fascinating life he had leading gemmological research from the first gem testing laboratory in the world. Delving into the zircons in the 1930s, collaborating with Professor Chudoba and jointly unravelling the mystery of the three zircon types. Anderson bridged the Atlantic to encourage gemology (with one m) in the persons of Liddicoate and Crowningshield. It was Basil Anderson who, as a chemist, created the first refractometer fluid over 1.6, even up to an RI of 2.2, in the process of which he set fire to himself, and rather than waste a taxi fare, he leapt on a London bus with smoke coming from his clothes, hospital bound. What a man. What a gentlemen, who welcomed me when I first visited the Hatton Garden laboratory in 1969 and was taken for lunch. I was in heaven. Basil introduced me to the other lab members: Robert Webster, author of the large tome Gems which also still sells today. Then there was A.C.D. Payne who did so much work in the laboratory, especially measuring the dispersion of gems to four decimal places by the process of minimum deviation.

Today's gemmologists can explore and indulge in the Photoatlas of inclusions in Gemstones, and The microworld of Diamonds by John Koivula – four volumes in all and which succeeded the first of its kind by Eduard Gubelin. All necessities in today's libraries.

When and where did you first lecture in the US?

Gem-A always participated in the Tucson Gem & Mineral show every year in Arizona. I was honoured to be invited to join them for the first time in 1989.

Is there anywhere of gemmological significance that you wish you had visited?

The far north of Canada to see at first hand the gem treasures being unearthed by Brad Wilson, including the cobalt blue spinels, the colour of which cries out as if to proclaim synthetic, and yet natural they are and can be distinguished by the spectrum gap width Spec 520 and 523 on page 220 of Gem Testing Techniques.